How Money Muling Works(4)

Vulnerability to Muling

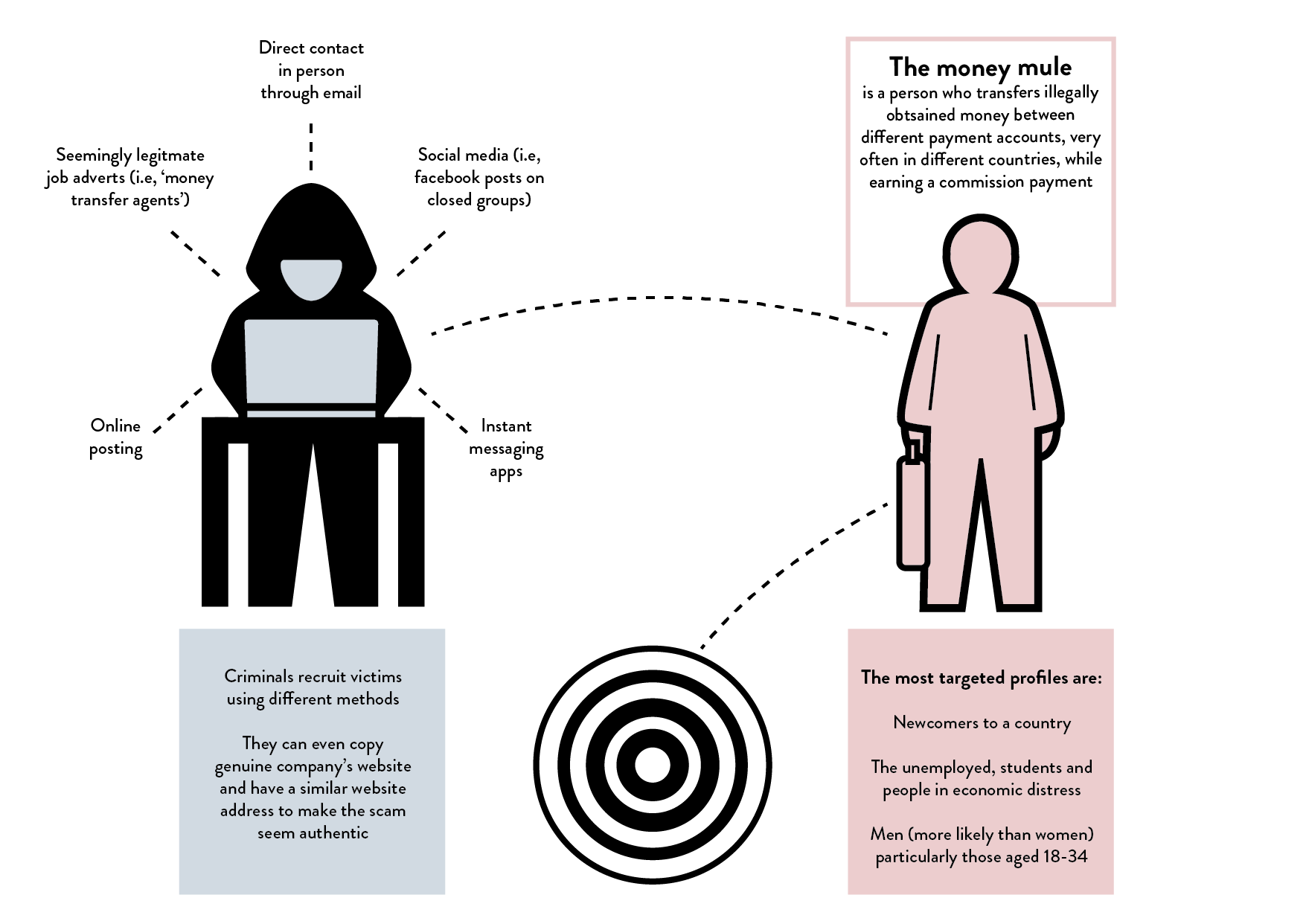

The unemployed and new immigrants from developing to developed countries have been major targets for muling operations for some time; financial desperation provides a motivation in both cases, and in the second, there is likely to be a lack of cultural understanding that criminals can exploit. However, there is an increasing trend in Europe towards the exploitation of young people and students, driven by their high levels of aspiration and low incomes, perceived naïveté, and accessibility online. According to a report in April 2018 from CIFAS, the UK-based not-for-profit fraud prevention group, 2017 saw:

An 27% increase in the number of 14-24 year olds being used as money mules. Many of these young people were students, promised substantial payments for little effort.

An 11% rise in the number of accounts believed to have been used by money mules (32,000 plus in total)(5).

In the UK, young people are also increasingly becoming the targets of identity fraud, leading to the misuse of their accounts by money launderers. At the Treasury Select Committee hearing, representatives from Santander noted that the young were particularly vulnerable to having their accounts being used for muling without their knowledge because so many of them take a lax approach to data security; according to Santander’s research, 85% of 18- to 25-year-olds had shared financial information online(6).

The Consequences of Muling

The consequences of becoming a money mule can be harsh, even if the mules are not aware of the ultimate rationale behind the transfers. Regardless of their level of knowledge, they will have played a crucial role in a financial crime, and as such are liable to criminal charges in most developed jurisdictions. In the UK, for instance, muling can lead to a prison sentence of up to fourteen years; in June 2018, the UK group Financial Fraud Action reported on a case of a 26 year old man sentenced by a London court to a year in prison for two mule transactions that totalled at £28,000(7).

Even if criminal charges don’t arise, there is still the risk of long-term financial exclusion and limitations on career prospects. In April 2018, the BBC reported on the case of an anonymous teenage girl, ‘Holly’, who had been targeted by online mule recruiters, or ‘Fraud Boys’ as they are known, on Instagram and Snapchat, but had been caught out by bank staff when depositing a large amount of cash into her account. According to the report, Holly has struggled to get a bank account since, and has had to ask her employers for payment by cheque, which can only be cashed - at substantial cost - in payday loan shops(8).

The Risk to FinTechs

Money mules are a problem for all financial services providers,. Research by Europol and Eurojust in 2016 suggests that 90% of money-mule transactions were linked to cybercrime. This included phishing and malware attacks, but also online shopping/e-commerce fraud and payment card fraud, typologies experienced by certain types of FinTech products largely due to the nature of their customer base(9):

Young people and students are attracted to products designed specifically to appeal to their needs, many FinTech products are seeing significant traction amongst this demographic. Other groups such as new immigrants or those seeking access to financial services might also be attracted to using online services which do not require lengthy verbal interactions with in-branch bank staff and offer products that are designed to address the imbalance of financial exclusion.

Criminals are aware of these developments, and it’s possible that they will focus increasingly on the recruitment of FinTech customers, particularly as other routes, via traditional institutions are closed off for them. This highlights the increasing need for close collaboration and joint working between financial institutions of all types to combat this type of crime.

Detecting Mules

The first consideration is awareness of the issue, and factoring it into your risk assessment and appetite. If your firm is focused on building a client base in the vulnerable demographics, then you need to make sure you explicitly recognise the risks and have the right controls to manage the nuances.

Every firm and product is different, and there is no generic approach to this, but it is worth recognising that it is difficult to identify all mules at onboarding, especially as some will onboard legitimately, being recruited as mule later (if you’re offering a product aimed directly at improving financial inclusion for example). This can be made harder if ‘at risk’ groups are part of your target customer segments. However, gaining a thorough understanding of the client during the Know-Your-Customer (KYC) phase and building that customer profiling in to a tuned customer risk assessment is a key to detecting problems later on. Because it is in the context of their expected behaviours that we judge what is unusual.

Unlike legacy banks, FinTechs are not going to catch mules out ‘in branch,’ as happened to ‘Holly’, mentioned above. Transactions take place online, so it’s important to have monitoring tools in place that can alert you to deviations in normal behaviour, along with an appropriately trained team to investigate those alerts and report them through a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) if necessary.

Utilising available data to identify and robustly investigate ‘at-risk’ accounts is a key control activity. Mule accounts are sometimes maintained through linked life-style payments to add an air of legitimacy so investigating account connections and leveraging data points such as common addresses (and others) can be a powerful way to proactively identify accounts for further review.

Additionally, building a suitable greylist or using industry databases such as CIFAS (or others) can provide a mechanism of detecting suspicious profiles at onboarding. Research suggests that accounts used during the later phases of mule activity in a network are more likely to be used by criminals more than once, presenting an opportunity to detect them via robust data sharing and blacklisting.

Increase Education and Prevent Mules

Prevention is often better than a cure so an important additional approach is to think about how FinTechs can help prevent the problem in the first instance. Reducing the pool of potential mules is a more cost effective ‘up-stream’ solution than tackling the effects of their activities. It also provides an opportunity for anti-financial crime professional to add something back to the community with clear positive social impact.

FinTechs have a unique advantage in the way they interact with their customer base and can play an important role in educating particularly vulnerable clients - especially young people - through explicit guidance during onboarding and throughout the customer lifecycle. Companies can engage in and support anti-muling campaigns, such as the EU’s European Money Mule Action (EMMA) imitative, or the ‘Don’t be Fooled’ campaign by the UK groups CIFAS and Financial Fraud Action (FFA)(10).

The young are especially in need guidance on what is ‘normal’ in the financial space, and arguably all financial providers have a duty of care in this regard. It does not take much to deliver simple key messages that reduce the risk to themselves and their clients: there is no legitimate reason to allow someone else to move their money via your account, however convincing they might be. There a three simple pieces of guidance FinTechs can give to their customers:

If you get offered a job or income, research any potential employer

Don’t respond to adverts offering large sums of money, for minimal input

Don’t allow anyone to access your account or use you card/app

And if it sounds too good to be true - it is. Walk away or ignore them.

Get in Contact

If you would like to discuss the issues in this post, or wider anti-financial crime topics in an increasingly digital FinTech world, please feel free to get in touch with one of our team or at contact@fintrail.co.uk.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/feb/13/banks-close-thousands-of-money-mule-accounts-mps-told

https://www.europol.europa.eu/crime-areas-and-trends/crime-areas/forgery-of-money-and-means-of-payment/money-muling

https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2018/01/12/2197610/fintech-as-a-gateway-for-criminal-enterprise/

https://www.europol.europa.eu/activities-services/public-awareness-and-prevention-guides/money-muling

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/personal-banking/current-accounts/fraudsters-target-cash-strapped-students-use-money-mules/

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/feb/13/banks-close-thousands-of-money-mule-accounts-mps-told

https://www.financialfraudaction.org.uk/news/2018/06/06/sentencing-of-26-year-old-money-mules-from-enfield-serves-as-stark-warning/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-43897614

https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/europe-wide-action-targets-money-mule-schemes

https://www.moneymules.co.uk