Key Points

1. Global policymakers have set their sights on cryptocurrencies, signalling that tackling the related financial crime risks is a major security priority

2. With the adoption of the Fifth Money Laundering Directive (5AMLD), cryptocurrency exchanges and wallet providers across the EU will soon face direct regulatory scrutiny and must ensure that they have appropriate financial crime risk management frameworks in place

3. In countries such as the US, where crypto-related AML/CTF regulation has already been in place for some time, regulators have indicated that they will intensify scrutiny of crypto businesses

4. Banks and other financial institutions are also facing pressure from regulators to manage their exposure to cryptocurrencies and related risks

5. The foundations for implementing a successful risk-based approach to cryptocurrencies rests on several pillars: conducting thorough risk assessments; defining risk appetite; cultivating staff competency and subject matter expertise; developing robust governance arrangements; developing, deploying and testing bespoke tools; and collaborating with industry peers

6. In this briefing, FINTRAIL explores how companies can successfully manage cryptocurrencies’ unique financial crime risks in an innovation-friendly manner

Introduction

The EU’s adoption of the Fifth Money Laundering Directive (5AMLD) in July 2018 marks an important moment for cryptocurrency businesses across Europe. By January 2020, EU member states must bring crypto exchanges and custodial wallet providers within the scope of their anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regulation.

The so-called ‘Wild West’ environment for crypto businesses is coming to an end.

5AMLD will put the EU’s crypto industry on par with peers in the US, where the Financial Crime Enforcement Network (FinCEN) clarified in 2013 that crypto exchanges are subject to AML/CFT regulation. Many in the EU’s crypto industry have attempted to get ahead of the curve.

Even prior to 5AMLD’s adoption, some crypto businesses across the EU had implemented AML/CFT policies and procedures, demonstrating their intention to be responsible actors. Europol has noted that, even absent formal regulation to date, many crypto exchanges across the EU, ‘aim to comply with AML requirements regarding customer due diligence and transaction monitoring . . . [and] many have shown themselves to be willing and capable of supporting [law enforcement] investigations.’

5AMLD nonetheless marks a turning point. EU crypto exchanges and wallet providers can’t merely be compliant on paper or on a voluntary basis any longer. They will soon be expected to demonstrate to regulators that they are actively managing their financial crime risks in a proportionate and effective manner. Failure to do so could mean fines or other penalties for crypto businesses that fail to meet regulators’ expectations.

In countries where crypto-related regulations are already in place, such as the US, signs point to a climate of intensifying regulatory scrutiny. In March of 2018, FinCEN issued guidance stating that the exchange of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) falls within its remit. In April 2018, New York’s Attorney General’s Office launched an inquiry into the accountability and transparency of crypto exchanges, requesting that thirteen major crypto exchanges disclose information about the nature of their compliance frameworks, including their AML/CFT programmes.

‘Treasury’s FinCEN team and our law enforcement partners will work with foreign counterparts across the globe to appropriately oversee virtual currency exchangers and administrators who attempt to subvert U.S. law and avoid complying with U.S. AML safeguards 1.’

- Acting FinCEN Director Jamal El-Hindi, July 2017

It’s not only crypto exchanges that are coming under the microscope. Regulators are putting increasing pressure on all financial institutions to manage cryptocurrency risks. In June 2018, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) published a letter to firms in which it set out its expectation that banks and other financial institutions should evaluate and manage the crypto-related financial crime risks they face.

Beyond the US and Europe, from Canada to Japan to Australia and beyond, regulators are taking a closer look at the nature of cryptocurrency risks and how the financial sector is managing them. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is currently reviewing the applicability of global AML/CFT standards to cryptocurrencies, demonstrating the renewed will of global policymakers to tackle the perceived risks.

‘The global regulatory environment for virtual currencies/crypto-assets is changing rapidly. This may make it challenging to ensure a consistent global approach, which could increase risks. Given the highly mobile nature of virtual currencies/crypto-assets, there is a risk of regulatory arbitrage or flight to unregulated safe havens.’

- FATF Report to the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, July 2018

In this environment, it may be tempting to find quick fixes and to address new risk management challenges with old compliance solutions. Unfortunately, the same old approaches won’t work. Cryptocurrencies present unique financial crime risk management challenges that warrant unique solutions. A thoughtful risk-based approach to cryptocurrencies requires thinking outside the box.

In this briefing paper, we share our thoughts about how firms in the crypto industry and in the broader financial sector can meet the challenge.

The Crypto Industry

Crypto businesses need to keep in mind that ‘compliance’ is not just about ticking boxes.

Best practice in AML/CFT is about thoughtfully managing risk. A well-calibrated risk-based approach can allow a crypto exchange or wallet provider to establish a truly comprehensive financial crime risk management framework that protects the integrity of its business, reduces exposure to financial crime and mitigates regulatory risk.

We’ve identified five key areas that can help a crypto business build a best-in-class risk management framework.

#1 Assessing Risk

A well-designed risk based approach starts with a thorough financial crime risk assessment. For crypto businesses, a risk assessment that takes account of the unique features and challenges of crypto products and services is essential. What’s more, it is important to develop a risk assessment framework that is scalable and can be used to evaluate changes in risk exposure as a company grows.

Current regulatory guidance, such as the UK’s Joint Money Laundering Steering Group (JMLSG), sets out factors to consider when undertaking a firm-wide risk assessment:

• Geography – Crypto businesses should assess risks related to where they are located and where they offer services. For example, is a crypto exchange registered in a jurisdiction with a strict regulatory environment, and how does this operating environment impact its risk profile? Is the platform accessible from jurisdictions subject to international sanctions? Is the service available in countries with high levels of terrorist financing?

• Customers – A crypto business should also consider whether factors about its specific customer base could impact its overall risk profile. For example, does it have any customers who are politically exposed persons (PEPs)? If so, who are those PEPs and does their source of wealth present any red flags? Are customers who are nationals of countries associated with high levels of human trafficking creating accounts in large numbers, and if so, do those accounts present signs of unusual activity?

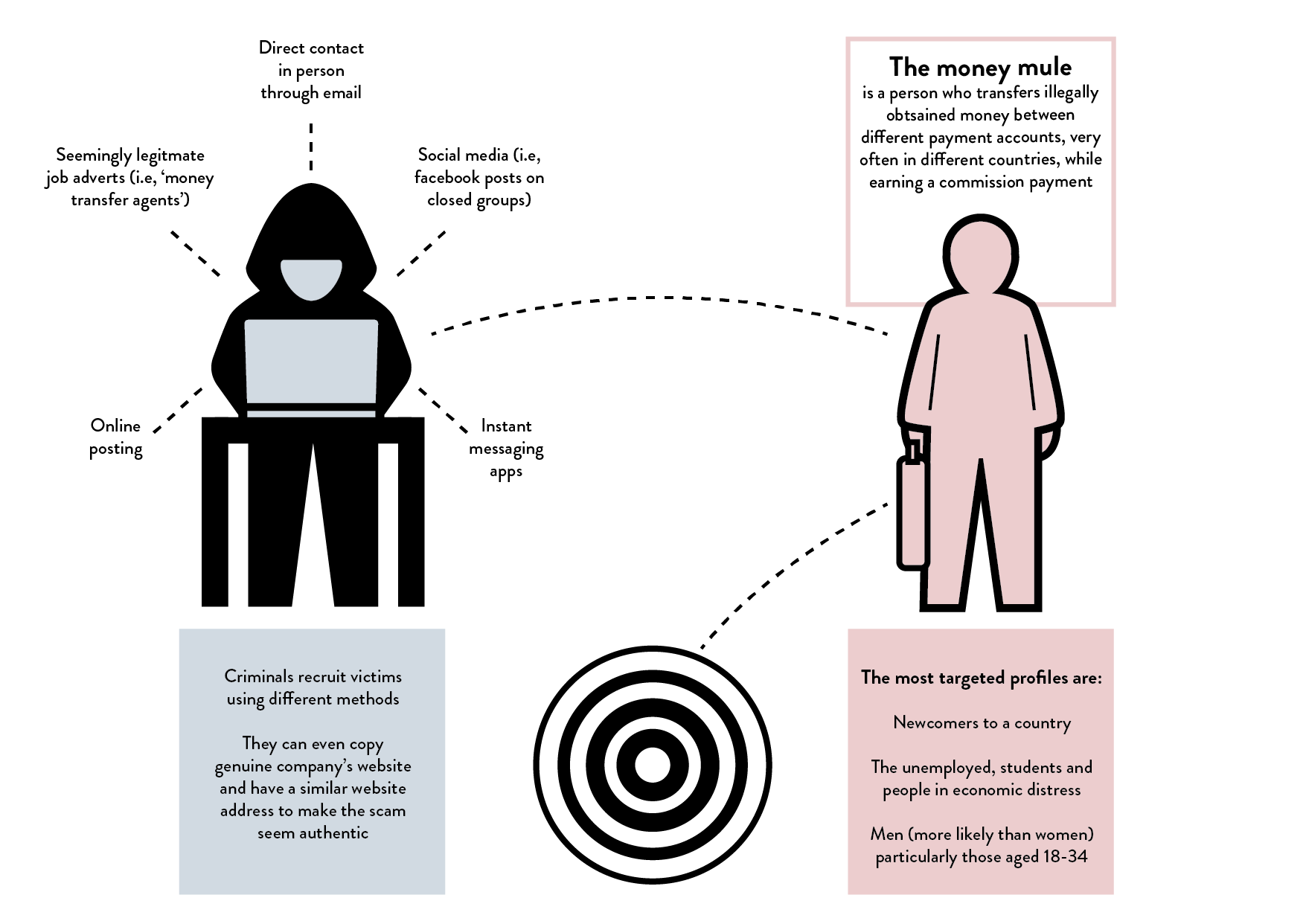

• Product – A crypto business needs to consider how any product features might impact its risk exposure. Does the product enable the rapid conversion of fiat currency to crypto in a way that might prove attractive to money launderers? Is the product vulnerable to high value money laundering, or do its features present a risk of lower-value money mule activity that can be pervasive but difficult to detect?

• Delivery channel – A crypto business also needs to think carefully about the risks related to how customers access its product or platform. Is it only accessible online? Or does the product involve Bitcoin ATMs or other physical infrastructure that customers can use?

In addition to assessing these general risk categories, crypto businesses should think carefully about the money laundering and terrorist financing risks that their specific offerings present. For example, whether they provide an online exchange service, a crypto ATM network or crypto prepaid cards, crypto businesses will face unique money laundering typologies and criminal vulnerabilities that are highly specific to their business type. Recent cases suggest that criminals are becoming savvier in exploiting a diverse range of crypto-related products and services, seeking out platforms that allow them to engage in increasingly complex money laundering schemes. Developing bespoke risk management solutions requires understanding these typologies in detail.

Crypto business should also assess the financial crime risks around the types of cryptocurrencies they provide. For example, privacy coins with high levels of anonymity such as Monero may present unique risks and challenges. It may prove challenging to monitor customer activity where these coins are present. Crypto exchanges that offer privacy coins to customers need to be aware of the resulting impact on their risk profile.

It’s important to remember that a risk assessment process should be supported by a sound methodology that enables a company to understand the evolution of its risks over time. This should include:

• Developing a logical approach to measuring inherent and residual risks;

• Ensuring risk assessment findings are thoroughly documented and presented clearly to senior management; and

• Having processes in place for updating the risk assessment, in whole or in part, when new business lines and products are launched, geographical expansion occurs or other trigger events arise.

‘Risk management generally is a continuous process, carried out on a dynamic basis. A money laundering/terrorist financing risk assessment is not a one-time exercise. Firms must therefore ensure that their risk management process for managing money laundering and terrorist financing risks are kept under regular review.’

- JMLSG, Guidance for the UK Financial Sector, December 2017

#2 Defining Risk Appetite

When a business understands its risks, it can decide which risks it finds acceptable, and those it finds too high.

A financial crime risk appetite statement can allow a crypto business to scale and develop new products and services in a thoughtful manner that ensures commercial goals are achieved without taking on excessive risk. As the Financial Stability Board has indicated 2, a good risk appetite statement can achieve several goals, including:

• Setting quantitative measures that track exposure to key risks, enabling proactive mitigation of risks before they become unacceptably high;

• Establishing limits to risk taking so that staff have a clear understanding of unacceptable risks;

• Defining staff members’ roles and responsibilities for mitigating risks; and

• Providing a baseline against which assurance functions can test that systems and controls are enabling the company to operate within its risk appetite.

By clearly defining the levels of risk they are willing to assume, a company’s senior management can establish a clear ‘tone from the top’ and foster a strong company culture. Failure to do so can result in a lax risk management environment that leaves the company exposed to reputational and regulatory risk.

‘A sound risk culture will provide an environment that is conducive to ensuring that emerging risks that will have material impact on an institution, and any risk-taking activities beyond the institution’s risk appetite, are recognised, escalated, and addressed in a timely manner.’

- Financial Stability Board, Principles for An Effective Risk Appetite Framework, November 2013

#3 Building a Compliance Team and Governance Arrangements

A strong company culture on financial crime is only possible if supported by a competent and effective team of suitably qualified AML/CTF compliance professionals.

‘One of the most important controls over the prevention and detection of money laundering is to have staff who are alert to the risks of money laundering/terrorist financing and well trained in the identification of unusual activities or transactions which may prove to be suspicious.’

- JMLSG, Guidance for the UK Financial Sector, December 2017

Even the smallest crypto companies should ensure that they have adequately experienced staff who understand financial crime risks, regulatory requirements and appropriate control measures. To this end, it is important to make sure that staff have received appropriate training. As the UK’s JMLSG3 advises, training should include ensuring staff awareness of:

• The company’s risks, as identified in its financial crime risk assessment;

• The company’s financial crime policies, procedures, systems and controls;

• AML/CTF regulatory requirements applicable to the company, and the consequences of breeching those requirements;

• The types of high risk customers the company encounters, and enhanced due diligence (EDD) measures that are in place to manage them; and

• Red flag indicators of suspicious activity specific to the company’s product and service offerings, and procedures for filing suspicious activity reports (SARs).

Larger companies should think carefully about how to structure their compliance functions so that risks are managed appropriately, and to ensure that senior management can monitor those risks over time. Compliance teams should be suitably resourced and visible within the company.

This may be accomplished, in part, by establishing financial crime risk committees that are comprised of senior risk and compliance staff and that review key management information to assess the effectiveness of controls and identify emerging risks. Robust governance arrangements can ensure that risk management functions are on the front foot against financial crime and are not merely reactive.

#4 Choosing and Tuning Tools

To be effective, a financial crime compliance team must be more than just impressive-sounding titles. Compliance functions must develop and utilise effective AML/CTF policies and procedures whilst having access to systems and controls that are proportionate to the risks their business faces.

Policies and procedures should be developed with the aim of mitigating a company’s risks as identified in its risks assessments. This could include, for example, having in place specific EDD measures for identifying customers’ source of wealth where less transparent products or services are used.

Financial crime systems and controls – such as identification and verification tools, transaction monitoring systems and sanctions screening solutions – should be appropriately calibrated to ensure a firm can operate within its risk appetite.

Bitcoin ‘track and trace’ forensic tools have also been developed and are already assisting many crypto industry participants in identifying and managing risks.

These systems and controls should be subject to regular audit and testing to ensure they mitigate key risks and meet regulatory expectations. As JMLSG notes4 , effective systems and controls are generally characterised by factors such as:

• Alignment with regulatory requirements and expectations;

• Appropriate resourcing; and

• Competent staff operating the controls.

Whether a company chooses to undertake internal or external audit, it needs to be able to demonstrate that systems and controls are compliant whilst also enabling it to manage its risks in practice.

#5 Working with Partners

Strength is in numbers, and crypto businesses can bolster their defences against financial crime by sharing information with their industry peers.

At FINTRAIL, we’ve co-founded the FinTech Financial Crime Exchange (FFE), a partnership of over 50 UK FinTech companies, including several of the UK’s leading cryptocurrency firms.

Through the FFE, crypto and other FinTech companies can share information on financial crime typologies they encounter and best practices for prevention and deterrence.

Proactive involvement in industry partnerships, self-regulatory organisations and other similar platforms can enable a company to stay on the front foot against financial crime.

![Figure 1 - Synthetic Opioid Drug Poisoning Deaths, per 100,000 of US Population 2011-2016, (Source CDC)[10]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ea58d4cd0f685ecfe1a0c4/1549029440683-QQMY6PZ90P3WGU0YOZ5K/Fentanyl+white+paper_Drug+deaths.png)